Key Findings

- December economic data maintained the economic resilience narrative after labor and inflation data ended the year on a high note. The first estimate of Q4 GDP growth points to a U.S. economy that is entering 2025 on solid ground.

- Financial markets had a solid start to the year, as the rates market ended January with slightly lower yields, while equities continued to perform strongly despite the “DeepSeek” induced volatility.

- With the change of the guard in Washington D.C. there has been a renewed interest in ending the conservatorship of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. We provide a review of the state of play and the key issues that will need to be addressed while emphasizing that any privatization effort will take time.

The U.S. Economy

Economic Growth and Inflation

The advance estimate of gross domestic product (“GDP”) released last week painted a U.S. economy that is entering 2025 in a position of strength. Economic growth came in at 2.3% seasonally adjusted annualized growth rate (“SAAR”) in Q4, capping off 2024, in which GDP expanded by a healthy 2.8% year-over-year (“yoy”).

The growth momentum in Q4 was driven by a consumer that remains confident and willing to spend. The 4.2% SAAR increase in consumer spending was broad-based, with significant contributions from both goods (6.6% SAAR) and services (3.1% SAAR). Notably, durable goods consumption surged 12.1% SAAR in the quarter, the most notable increase since Q1 2023, fueled by strong spending on motor vehicles and recreational goods. Meanwhile, fixed non-residential investment declined 2.2% SAAR driven by weakness in structures and equipment spending. In addition, growth was held back by a drawdown in inventories, which subtracted roughly 0.9 percentage points from the quarterly annualized growth rate.

Despite the robust spending growth in Q4, slower income growth and declining savings, with the savings rate falling to 3.8% of disposable income in the December PCE report, suggest consumption should slow even before pricing impacts from tariffs levied and/or proposed by the Trump Administration.

The Federal Reserve's (“Fed”) preferred inflation gauge came in largely in line with expectations, indicating that monetary policy remains restrictive enough for a sustained, albeit slow, return to target inflation. The headline personal consumption expenditures (“PCE”) price index slowed to 2.55% yoy in December, while the PCE index excluding food and energy slowed to 2.79% yoy. Both indices are modestly below their December 2023 readings, underscoring the slow inflation progress seen in 2024.

Labor Market

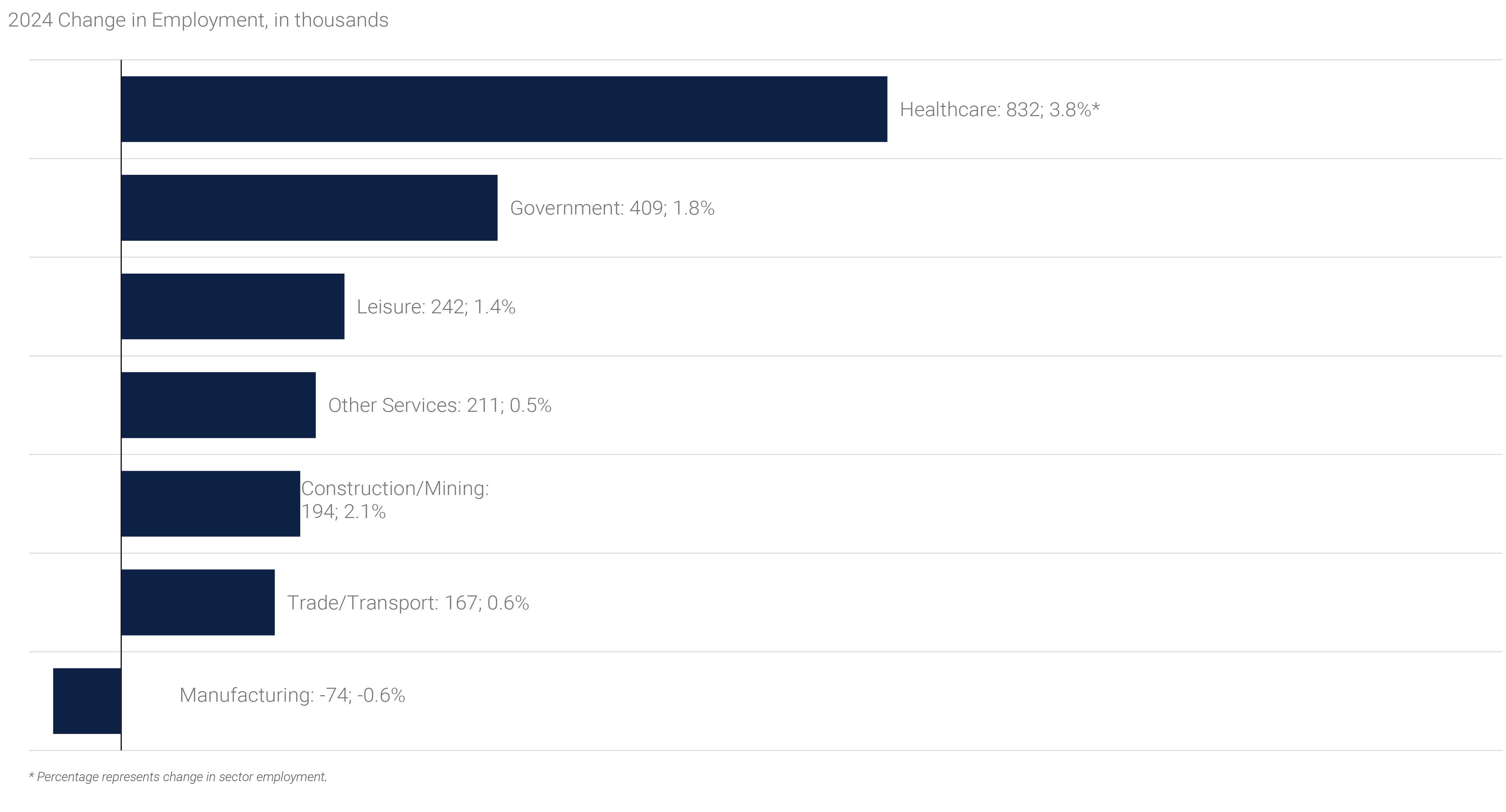

The employment data for the month of December ended 2024 on a high note, as nonfarm payrolls growth exceeded expectations for a second consecutive month. Employers hired 268,000 workers in December, with gains relatively healthy across industries. Manufacturing jobs offered a notable exception to the broad-based hiring, losing another 13,000 jobs in December and becoming the only major sector with job losses in 2024 (see panel 1). Looking back at the labor market in the second half of 2024, a strong September employment report was seen as an outlier in between softer July, August and October data, though the latter was impacted by hurricanes Helene and Milton. But strong November and December readings and a plateau in the unemployment rate, which ticked down to 4.1% from a 4.2% peak earlier in the year have changed the narrative about a deterioration in the pace of hiring – the biggest driver behind the onset of Fed rate cuts back in September – at least temporarily.

Panel 1:

2024 Labor Market Gains Driven by Healthcare, Manufacturing with Job Losses

While hiring has remained healthy, wage growth continues to moderate. Readings on the Employment Cost Index, the Fed’s preferred measure to track wage growth, suggested that aggregate labor compensation slowed to 3.8% yoy in Q4, down from 4.1% and 5.1% at the end of 2023 and 2022, respectively. The slower wage and benefit growth is driven by the private sector, which saw wages slow to 3.7% yoy, the lowest reading since Q2 2021. The slowing wage trajectory should give the Fed added comfort that inflation should continue to moderate, as various Fed officials have long discussed the close link between wage and service-sector inflation.

Financial Markets

Interest Rates and Volatility

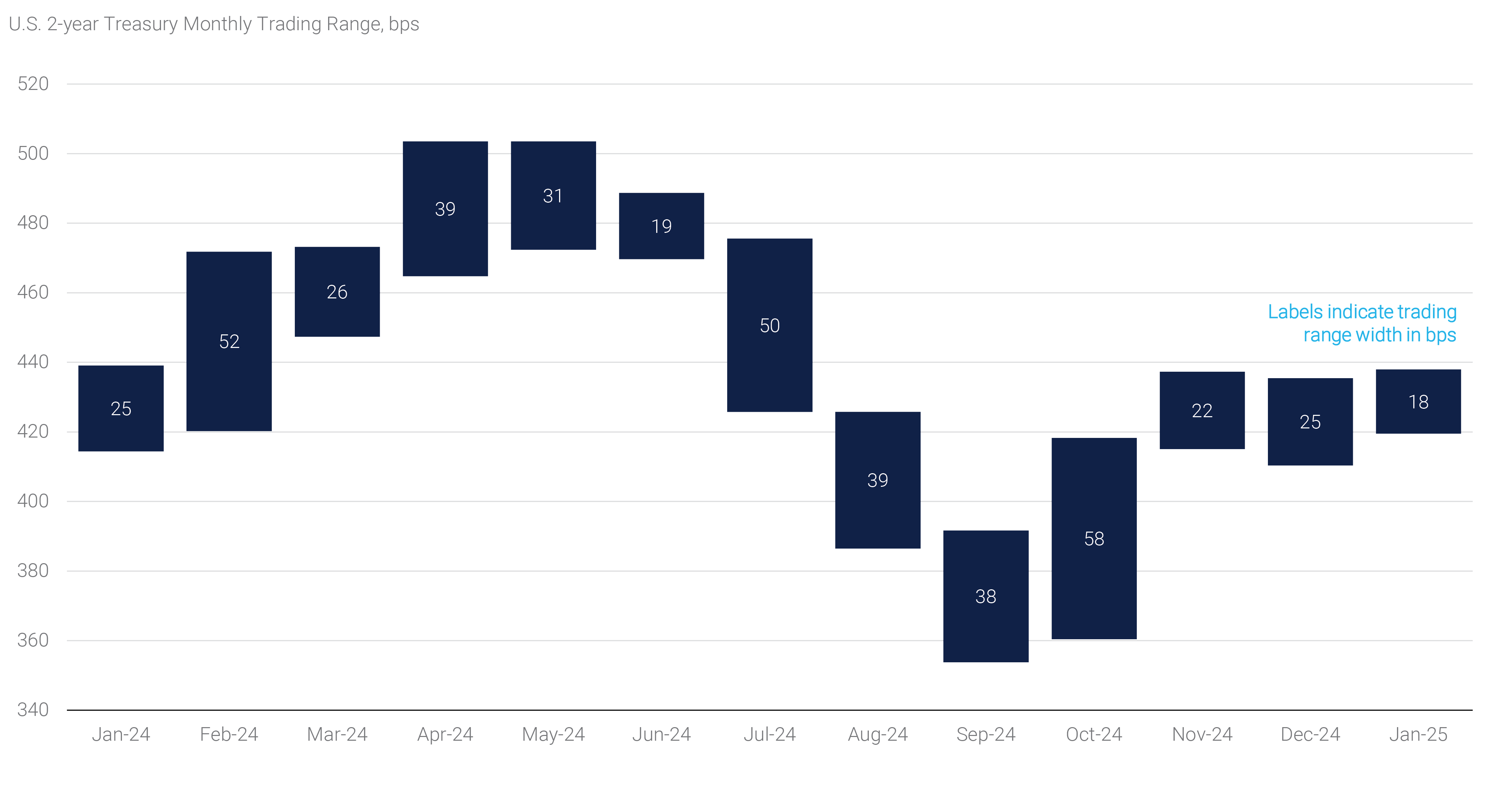

At the start of the year, policy uncertainty—both monetary and fiscal—was a key focus for fixed income markets, as investors closely tracked economic data and developments from the new administration. As a result, long-end Treasury yields traded in a wide range, rising to levels not seen since fall 2023 before reversing mid-month in response to softer inflation data. A broader risk-off sentiment in equities also drove safe-haven flows into U.S. debt, pushing yields even lower by the end of the month. The 10-year Treasury yield ended January at 4.54%, down by 3 basis points (“bps”), while the 2-year yield finished at 4.20%, declining by 4 bps.

Despite these movements, realized interest rate volatility remained relatively subdued as the Fed signaled it was pausing its easing cycle. At this month’s Federal Open Market Committee (“FOMC”) meeting, the Fed held policy rates steady, and Chair Powell noted that, although rates remain well above neutral, they are not in a rush to cut further. They would like to assess the effects of prior rate cuts and continue monitoring economic data before making further adjustments. This has helped to keep front-end yields anchored to the current level of Fed Funds as well as keep volatility low. The ICE BofA MOVE Index, a gauge of short-term U.S. bond market volatility, declined 8% in the month.

Panel 2:

2-Year Treasuries Remained in a Narrow Range

Agency MBS and Credit

Mortgage rates have been increasing since late September, surpassing 7% in January, highlighting the ongoing challenges to the housing sector. This led to limited refinancing activity and a light supply of agency mortgage-backed securities (“MBS”), which were easily absorbed by strong demand from money managers. Along with the decline in interest rate volatility in January, mortgage spreads traded in a tight range. The Bloomberg U.S. Mortgage-Backed Securities Index recorded a 4 bps excess return.

Credit markets have continued to perform well. Fourth-quarter earnings have so far exceeded expectations, and optimism around deregulation has further boosted momentum. Corporate supply and demand have also started the year on a strong note. Investment-grade corporate issuance set a record for January at $196 billion, surpassing the previous record of $194.5 billion set last year, and, despite a decline in risk sentiment from the equity market, appetite for new issues has remained robust. As a result, the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Corporate Bond Index posted an excess return of 13 bps in January.

Equities and Currencies

Equity markets experienced a volatile start to the year. The S&P 500 hit record highs mid-month, driven by stronger-than-expected earnings, a slower-than-expected tariff rollout, and strong consumer spending. However, news that China-based AI company DeepSeek had developed cheaper and more powerful models than OpenAI's led to a sharp risk-off reaction. The Nasdaq 100 dropped 3.5% in one day as investors worried about increased competition for U.S. AI and chip companies.

Despite this, equity markets ended the month higher, with the S&P 500 up 2.70% . The U.S. dollar (“USD”) continued its upward trend in January, with the DXY Index reaching its highest level in two years. The increase was driven by the same themes that have persisted since late 2024: robust U.S. economic growth, widening interest rate differentials, and the USD’s safe haven appeal amid global uncertainties. However, the USD’s strength eased mid-month following softer-than-expected inflation data and as the Japanese yen outperformed amid a rate hike from the Bank of Japan. Meanwhile, gold rallied to record highs as safe haven demand increased on the heels of President Trump’s tariff threats and growing fears of trade wars.

The Long and Winding Road to GSE Privatization

With President Trump’s return to the White House, attention has turned to the potential effort to end the conservatorship of the government-sponsored enterprises, specifically Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (the “GSEs”). Given the clear moves to privatize the GSEs in the waning days of Trump’s first term, many expect that there will be another push during his second term. The amendment to the Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements (“PSPAs”) in the final days of the Biden presidency and the post-election rally of the GSEs’ common stocks are examples of renewed interest in this issue.

Releasing the GSEs from government conservatorship is a complex and contentious issue that appears to have limited political and consumer upside. Moreover, recent proposals appear overly ambitious and politically infeasible. Thus, while the odds of a release may have risen, the timeline and ultimate viability of a privatization plan remain uncertain. There are also a handful of issues that should be clarified to avoid potentially harmful disruptions to the mortgage market as the GSEs currently guarantee roughly 46% of outstanding mortgage loans in the U.S.

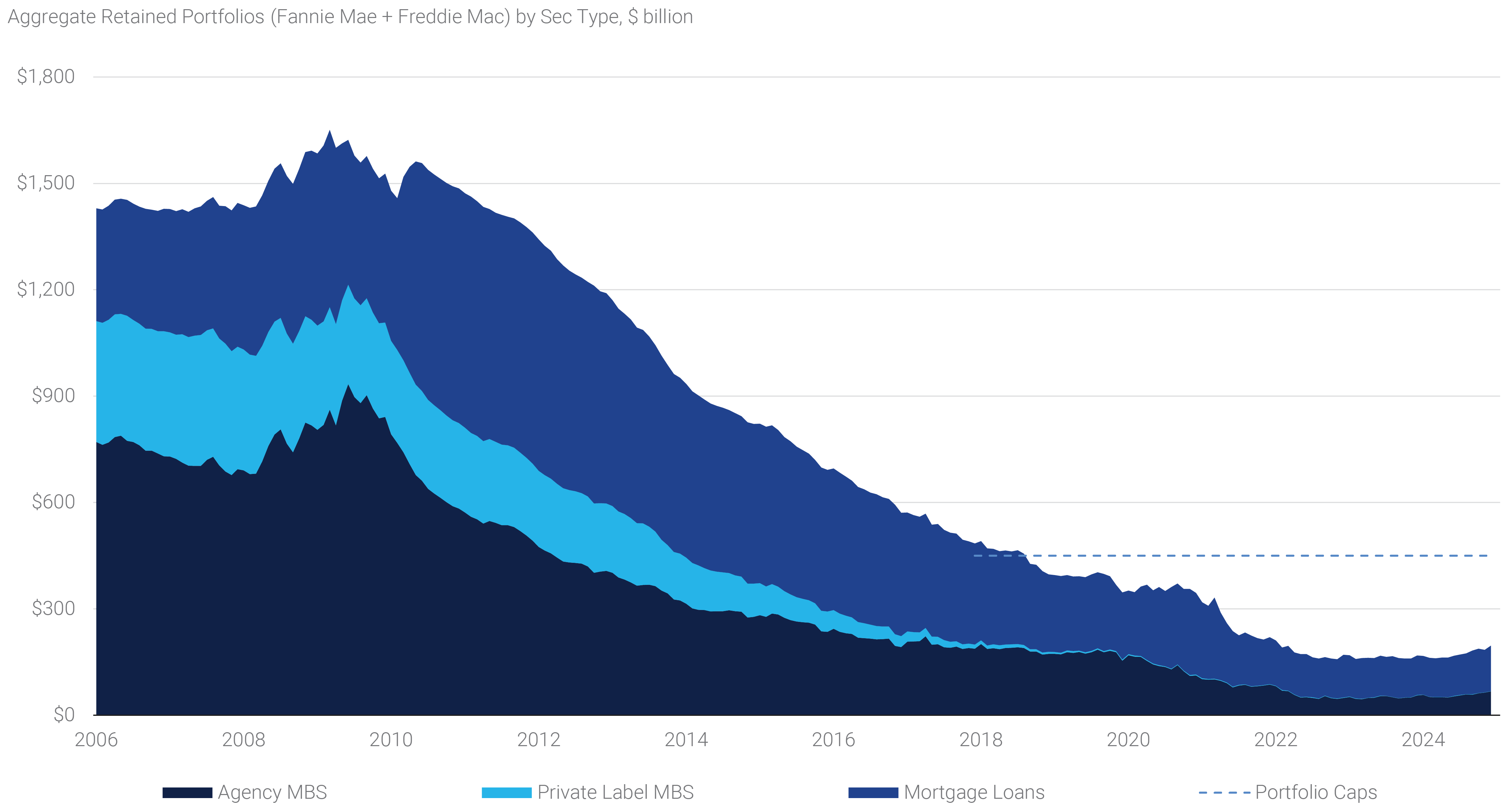

Taking a step back, it is important to understand how we got to where we are today. The GSEs were chartered by Congress with a clear policy objective to facilitate homeownership by increasing the availability of affordable mortgages. However, in the lead-up to the 2008 financial crisis, the GSEs imprudently over-levered themselves, including a significant increase in their retained mortgage portfolios (see panel 3). As losses mounted given sharp market value declines in both their guarantee and retained portfolios, their solvency came into question. The U.S. government placed the GSEs into conservatorship in September 2008, giving full operational control to a dedicated federal regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (“FHFA”). At the same time, the U.S. Treasury entered into PSPAs with the GSEs, committing to extend a large line of credit to ensure they could cover all of their liabilities. In turn, what had been viewed as an implicit government guarantee for their MBS effectively turned into an explicit one under the capital backing afforded by the PSPAs.

Panel 3:

GSE Retained Portfolios

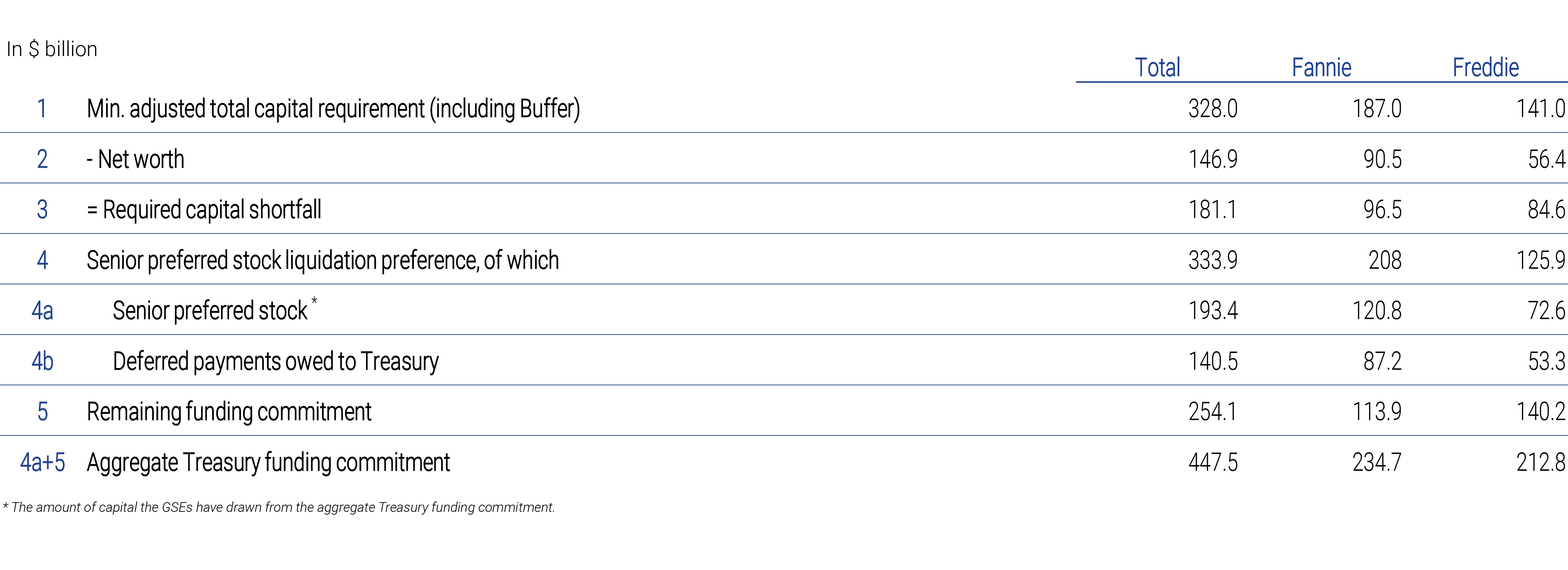

The initial PSPAs required the GSEs to make 10% dividend payments to the Treasury in exchange for their financial backing. Treasury also received warrants to purchase 79.9% of the GSEs’ common equity at a nominal strike price. As earnings were insufficient to cover the initially agreed upon payments, the PSPAs were amended multiple times. A 2012 amendment recalibrated the quarterly dividend to be essentially the GSEs’ quarterly net income and suspended the periodic fee for Treasury’s remaining funding commitment. Subsequent amendments waived dividend payments, allowing the GSEs to increase their net worth, which stood at a combined $146.9 billion as of Q3 2024 (see panel 4). The increased net worth, combined with a cleaner guarantee book, has led to the GSEs having a cleaner risk profile today. Nevertheless, they are still in a significant regulatory capital shortfall position. Moreover, foregone payments have also been added to Treasury’s liquidation preference, which stood at a combined $333.9 billion.

Table 1:

GSE Capital Overview as of Q3 2024

While the conservatorship of the GSEs was never meant to be permanent, making the impetus to privatize them reasonable, the question remains whether now is the time. Putting this question aside, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent

noted to lawmakers that GSE reform is not one of his immediate priorities and that when the time comes, implications will be carefully considered. He also said, “Treasury should be compensated for its past support of the GSEs.” Lawmakers have acknowledged the challenges of this issue, and some have indicated that they will work with an executive branch that will lead and put in the work necessary to do this the right way. These remarks are reassuring as we believe that a durable solution requires both administrative and legislative actions.

First and foremost, there needs to be clarity around the government’s role if the GSEs are to be released. Lack of certainty in this area – or worse the absence of an implicit or explicit government guarantee altogether or Treasury’s remaining $254 billion funding commitment – would raise questions regarding the GSEs’ business model and investor support for Agency MBS. Mortgage rates would likely be negatively impacted and hurt consumers. A privatization plan should address these issues including setting a fee for Treasury’s continued financial backing. Section 6.3 of the PSPAs prohibits any changes to Treasury’s funding commitment that would make existing bondholders worse off.

Furthermore, the taxpayer’s investment of over $330 billion (which cannot be easily written off)(1) would need to be resolved, the regulatory regime will need to be updated, and guarantee fees will need to be determined. Yet, as the GSEs continue to build net worth, there may come a time when the GSEs could meet current capital requirements and be in a position to be released. Given the role they play in the U.S. housing market, the complexity of the issue, and other more pressing policy priorities for the Trump administration, we would expect the push to privatize the GSEs to take time.