Key Findings

- With the change in government fast approaching, we believe the U.S. economy remains in a good place. Recession fears have largely abated as economic growth is once again poised to beat consensus estimates, inflation is trending back towards target even if progress has recently stalled, and the labor market has rebalanced but remains healthy.

- Yields rose and risk assets outperformed given the “Red Sweep” election outcome.

- Short-lived volatility in funding markets at quarter-end point to frictions that are preventing efficient financial intermediation. We discuss the issues and some of the solutions likely considered by policymakers.

The U.S. Economy

Economic Growth

Lifted by healthy consumer spending and steady business investment, initial fourth quarter data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (“BEA”) suggests that the U.S. economy remains on strong footing with 2024 economic growth tracking 2.7% year-over-year (“yoy”). This will mark a second consecutive year of strong economic growth despite elevated interest rate levels. Moreover, the Republican election sweep appears to have lifted consumer and business confidence by fostering hopes of a full extension of the 2017 tax cuts and a broad deregulatory environment, which could bode well for economic growth in early 2025. At the same time, some believe that the outlook remains more uncertain given the Republican sweep, as certain policy proposals – such as the potential mass deportation of illegal immigrants and broad-based tariffs on U.S. goods imports – arguably contain a wider range of outcomes than if the election had delivered a more split control of government.

Inflation

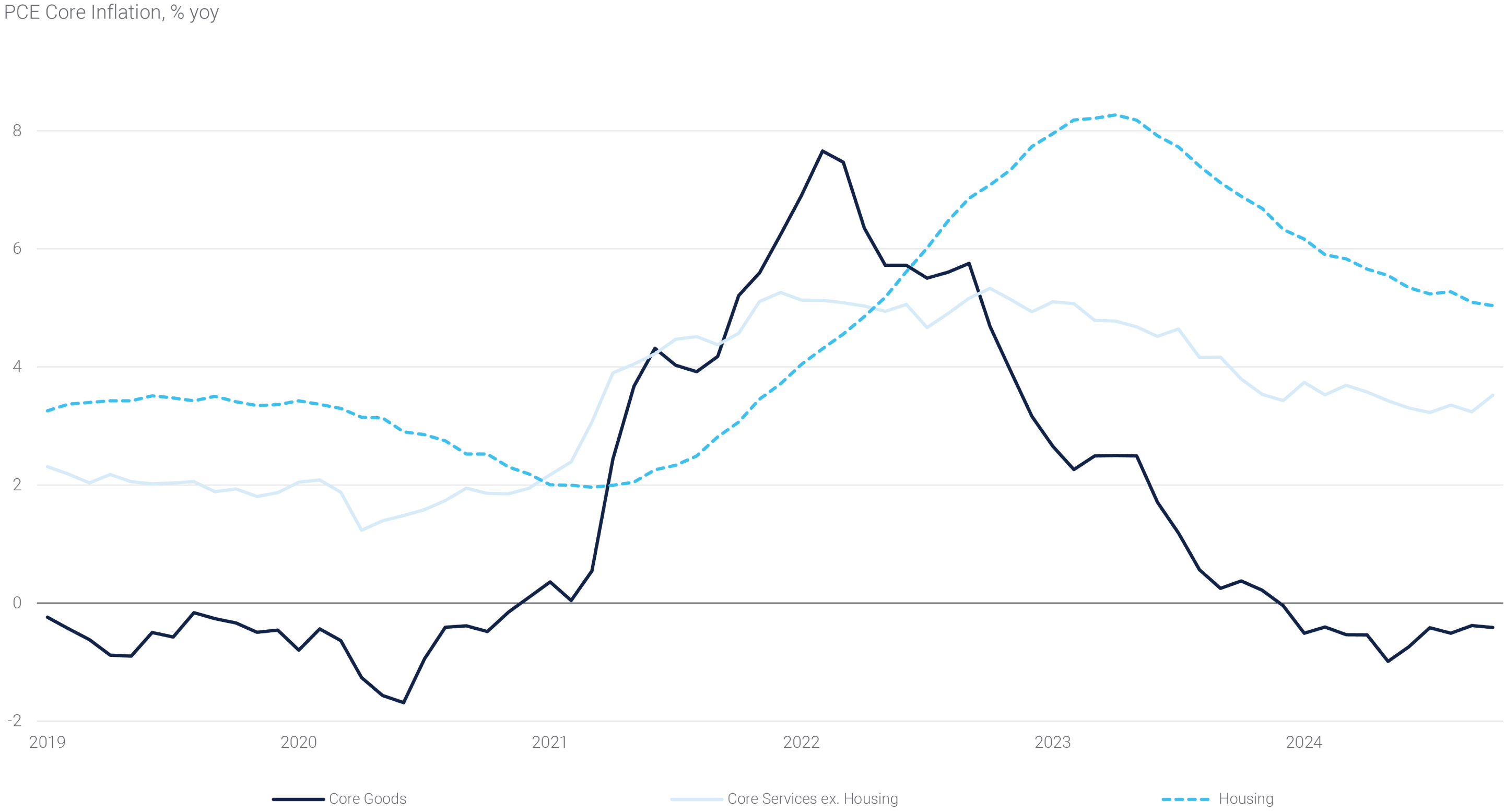

Inflation in the U.S. rose slightly in October, showing that the last mile in getting inflation back to target levels will likely be slow-going and uneven. As reported by the BEA, core personal consumption expenditures (“PCE”) inflation jumped to 2.8% yoy, while the headline measure came in at 2.3% yoy. Volatile components like airline fares, used auto prices, and portfolio management fees contributed to the increase in core PCE. Yet, sticky services inflation, particularly shelter inflation which keeps on running well above pre-pandemic levels, continues to be the main culprit behind the bumpy inflation moderation (see panel 1).

Panel 1:

Shelter Inflation Still Running High

Following October’s print, core PCE would now have to average an estimated -3 basis points (“bps”) the rest of the year to hit the Federal Reserve’s (the “Fed”) forecast of 2.6% Q4-over-Q4 from September’s Summary of Economic Projections, making a modestly higher revision at the December Federal Open Market Committee (“FOMC”) meeting a near certainty.

Labor Market

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, payrolls continue to moderate, as downward revisions and a weaker-than-expected reading of 12,000 jobs created in the month of October brought the 3-month average to 104,000 jobs. However, a blend of exogenous shocks including labor strikes, bad weather, and the lowest survey response rate since 1991 (47.4%) suggest that the trend in nonfarm payrolls was potentially understated in October. Of note, the unemployment rate held steady at 4.1% while unemployment insurance claims remain muted. Moreover, survey-based perceptions of the labor markets, such as the National Federation of Independent Business labor market number and the Conference Board Consumer Confidence labor differential have remained mostly unchanged. Altogether, according to the most recent data, the labor market appears to have returned to balanced supply and demand, and we believe it is stabilizing right here for now.

A strong macroeconomy and steady labor market along with a more uncertain inflation picture has forced a pivot from Fed policymakers, who have begun to signal slower rate cuts and a higher terminal rate unless inflation moves closer to the inflation target or the labor market deteriorates more meaningfully. Nevertheless, markets are still pricing high odds of a 25-bps cut at the December FOMC meeting but expect only 3 total 25 bps cuts by the end of 2025 with the secured overnight financing rate (“SOFR”) future implied rate rising to 3.89% since hitting a low point in early September (see panel 2).

Panel 2:

Markets Have Priced Rates at the End of 2025 in a Wide Range

Financial Markets

Interest Rates and Volatility

Interest rate volatility fell meaningfully in November as the uncertainty around the U.S. election lifted. U.S. Treasury yields initially climbed higher amid the Republican Party’s Election Day performance, better-than-expected economic data releases, and comments from Fed officials that suggested a slower pace of easing. The move was attributed to higher term premiums, or the compensation investors require to hold longer-term bonds, given the increased likelihood of fiscal expansion under the “Red Sweep” election outcome. The bearish momentum, however, stalled when 10-year Treasury yields reached 4.50%, a level they were unable to sustainably break through. Furthermore, yields retraced their post-election selloff at the end of the month as the market seemed to welcome President-Elect Trump’s choice for Treasury Secretary. Markets also reflect an expectation that the initial focus of the incoming administration will be on immigration and trade, whose impact on yields is less directional, rather than on taxes. Consequently, 10-year and 30-year Treasury yields both ended November 12 bps lower.

At the same time, expectations around Fed easing have been scaled back. Fed communication has grown more hawkish, with officials pointing to the strength in the real economy and suggesting a potentially higher neutral rate – the rate at which monetary policy is neither stimulative nor restrictive. Chair Powell has been consistent in his messaging that monetary policy will not be adjusted to a future potential change in fiscal policy. Yet, Fed members are weighing feedback from businesses, consumers, and markets to determine whether inflationary pressures are re-emerging. One-year forward one-year swap yields rose 11bps in the month, a sign that the market is pricing the Fed’s easing campaign to end at a higher rate than it did a month ago. Therefore, while front-end yields decreased, with 2-year Treasury yields finishing the month 2 bps lower, their decline was less pronounced compared to the longer end of the curve.

Finally, volatility in Treasury repo markets has been somewhat elevated, as dealers are anticipating constrained balance sheet usage over year-end and worries around dealer intermediation in the repo market have increased as discussed below. However, the election outcome raised the likelihood of a shift in the regulatory environment, in particular potential regulatory changes that could make owning or funding Treasuries less balance sheet punitive. Because of this, Treasuries outperformed the swap curve leading swap spreads to widen in anticipation of deregulatory headwinds.

Agency MBS & Credit

Agency mortgage-backed security (“MBS”) spreads tightened in tandem with other credit products in November, reversing the widening seen in October and delivering 56 bps in excess return. Despite outperforming Treasuries, MBS spreads remain wide relative to other spread products given the still elevated volatility. In addition, the supply/demand picture remains reliant on money manager inflows as bank and foreign demand remains tepid for now. Nonetheless, the picture has improved throughout 2024, and nominal spreads remain historically elevated.

Following the election, spreads across many credit products have reached all-time tights. The “U.S. exceptionalism” pro-growth theme has favored credit, leading investment grade corporate bonds to deliver an excess return of 49 bps(1) and high yield spreads to remain tight after hitting a multi-decade low in October. With $99 billion in new investment grade (“IG”) supply this month, 2024 has officially passed 2021 as the largest year of IG supply other than 2020. Looking ahead, there seem to be few reasons for this trend to reverse in the near term given very healthy demand following a strong corporate earnings season. Demand for U.S.

Equities & Currencies

Like other risk assets, equity markets have rallied on the heels of the election amidst expectations for a pro-growth, pro-cyclical administration emphasizing lower taxes and regulatory easing. The S&P 500 Index price was up 5.7% in the month led by consumer discretionary sectors. However, higher growth expectations have been partially offset by uncertainty related to tariffs, with shares of retailers and manufacturers that are reliant on imports coming under pressure. Additionally, as evidenced by the S&P 500 and Russell 2000 indices, small cap stocks have generally outperformed large cap stocks, with the former viewed as beneficiaries of a pro-cyclical administration. Under the same pro-growth themes, the U.S. Dollar has rallied post-election with the U.S. Dollar Index rising 1.7% in November (see panel 3). This follows a strong performance of the Dollar against other major currencies in October, erasing the weakness seen throughout the third quarter. Tariff threats, a hawkish Fed bias, and solid economic data should support Dollar strength through year-end. At the same time, cryptocurrencies have soared as the incoming Trump administration has taken a more welcoming approach to digital currencies. Bitcoin has risen over 40% since the night of the election, while other crypto-related assets have risen concurrently.

Panel 3:

The U.S. Dollar Has Strengthened in Q4

Frictions in Funding Markets

Outside of the election, November market chatter focused heavily on frictions in funding markets. Following elevated repo market volatility at the end of September, market participants are now focused on what this could mean for year-end in December, when banks are in a more challenged position to extend balance sheet to their counterparties. We view the market volatility not as a sign of insufficient funding availability, but primarily as frictions in the “plumbing” of the system that may prevent the most efficient transmission of liquidity.

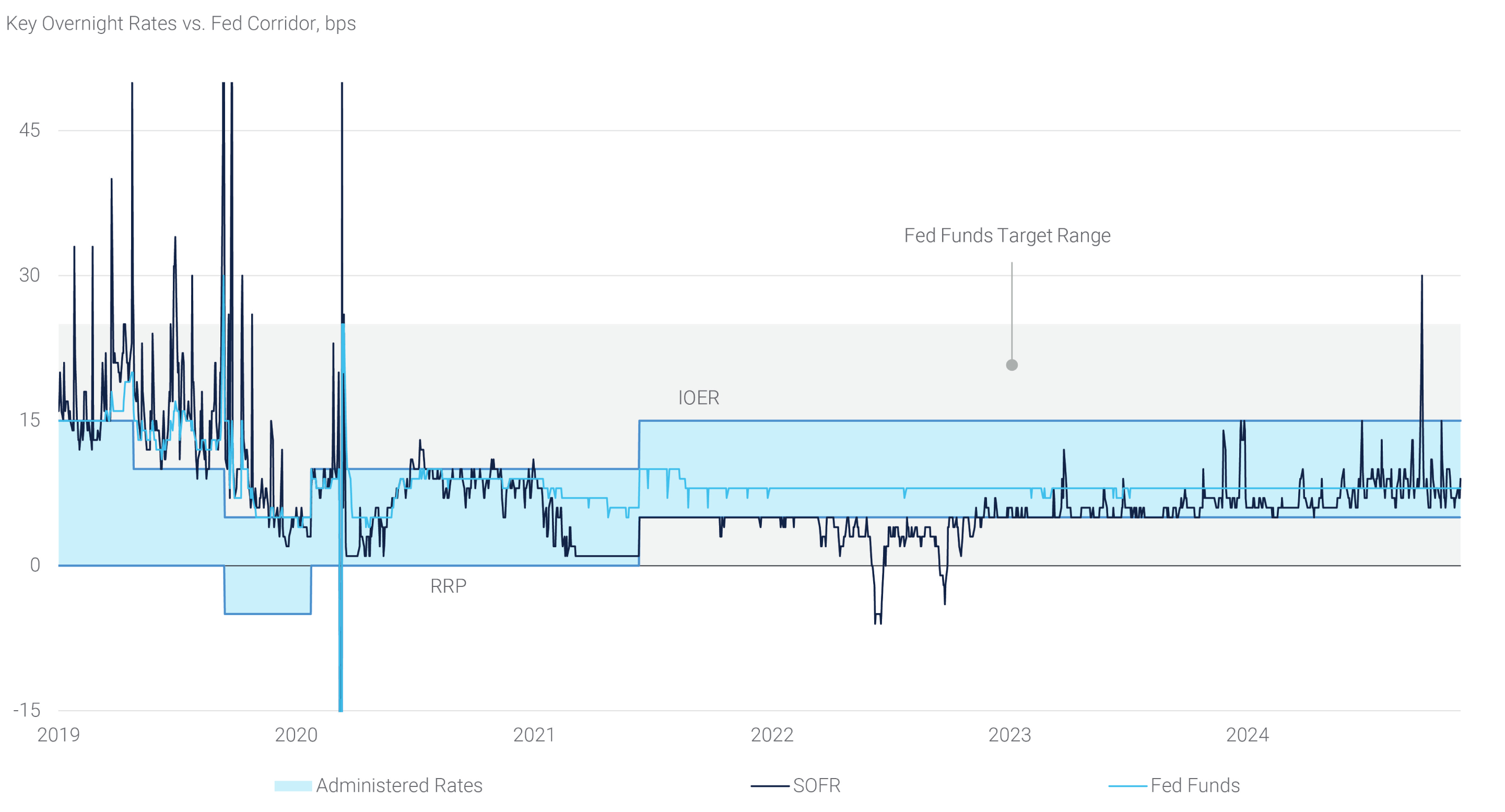

After nearly 30 months of quantitative tightening (“QT”) and the resulting declines in liquidity, reflected in reduced reverse repo take-up at the Fed and lower bank reserves, Fed officials have characterized front-end funding as exhibiting typical behavior for periods of less abundant reserves, but not showing signs of scarcity just yet. Unsecured front-end rates have not moved, even though secured repo rates have seen some pressure (see panel 4). Nonetheless, given that solutions to improve the plumbing are available, ignoring the growing signs of pressure could be viewed as poor risk management. We believe that central bankers will work to implement solutions that “grease the wheels” of intermediation.

Panel 4:

Front-End Rates Show More Volatility

One first and easy-to-implement solution would be to lower the overnight reverse repo (“RRP”) rate, which acts as the floor in the Fed’s corridor system, to at least the bottom of the Federal Funds target range. This move would create fewer incentives for money market funds to keep funds parked at the Fed and could free up to roughly $216 billion(3) parked in the facility on average over the past month to be lent in other markets such as repos. Fed officials discussed this idea at the November FOMC meeting, suggesting a change to help alleviate funding pressures could come before year end.

Another solution is to adjust the Fed’s standing repo facility (“SRF”) to enhance its effectiveness. The SRF is designed to support liquidity conditions by lending cash against Treasury collateral should repo market interest rate spike, therein creating a ceiling on interest rates. The facility saw its most meaningful utilization on September 30, but – at $2.6 billion – it remains a very small part in the much bigger repo market given multiple shortcomings. For one, the SRF currently does not allow primary dealers and large banks to net their balance sheets, leaving them with potentially higher capital costs to intermediate flows. Also, settlement in the facility occurs late in the day, potentially too late for counterparties in need of cash earlier in the day to, for example, accommodate typical month-end Treasury coupon settlements. Lastly, counterparties might be cautious to use the facility given potential stigma associated with public disclosure rules as transaction data is released after a two-year period. Addressing these limitations in the SRF could encourage greater usage and establish a more effective upper limit on funding rates.

There are additional solutions to these plumbing issues that are more complex. For example, dealers must meet bank regulatory capital rules and liquidity ratios that can limit the amount of leverage provided to third parties. In general, there are good reasons for these regulatory constraints, but they can also prove inflexible during periods of stress. Exempting reserves, short-term overnight lending, and short-term Treasury debt from liquidity rules – similar to the temporary exemptions allowed during the pandemic – might also help intermediation, though these changes are likely more challenging to implement and require additional considerations.