Key Findings

- Economic data released in December showed the expected hurricane/strike bounce back in hiring and a U.S. economy that retains momentum heading into 2025.

- However, financial markets offered a lackluster end to what can otherwise only be described as a stellar year, particularly for equities.

- Treasury yield levels rose sharply to end near 2024 peaks as hawkish Federal Reserve (“Fed”) messaging, robust economic performance, and concerns about government debt weighed on fixed income markets.

- We discuss the rising estimates of the neutral rate of interest and their implications for interest rate markets going forward.

The U.S. Economy

Economic Growth

Economic data received in December maintained the prevailing narrative of a strong U.S. economy propelled by consumer spending. Real GDP for Q3 was revised up to 3.1% seasonally adjusted annualized growth rate (“SAAR”) from an initially reported 2.8% SAAR. Meanwhile, the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model estimate for Q4 currently stands at 2.4% SAAR, suggesting the economy remained nearly as strong as Q3 based on October and November data. Of note, the continued strength in the data led Fed officials to increase GDP growth for 2024 in their Summary of Economic Projections (“SEP”) to 2.5% -- one of the larger upgrades to current year economic growth in the history of the Fed’s projections. Growth continued to be driven by consumption, as October and November personal consumption expenditures (“PCE”) data imply Q4 combined goods and services spending expanded at 2.6% SAAR.(1)

Inflation

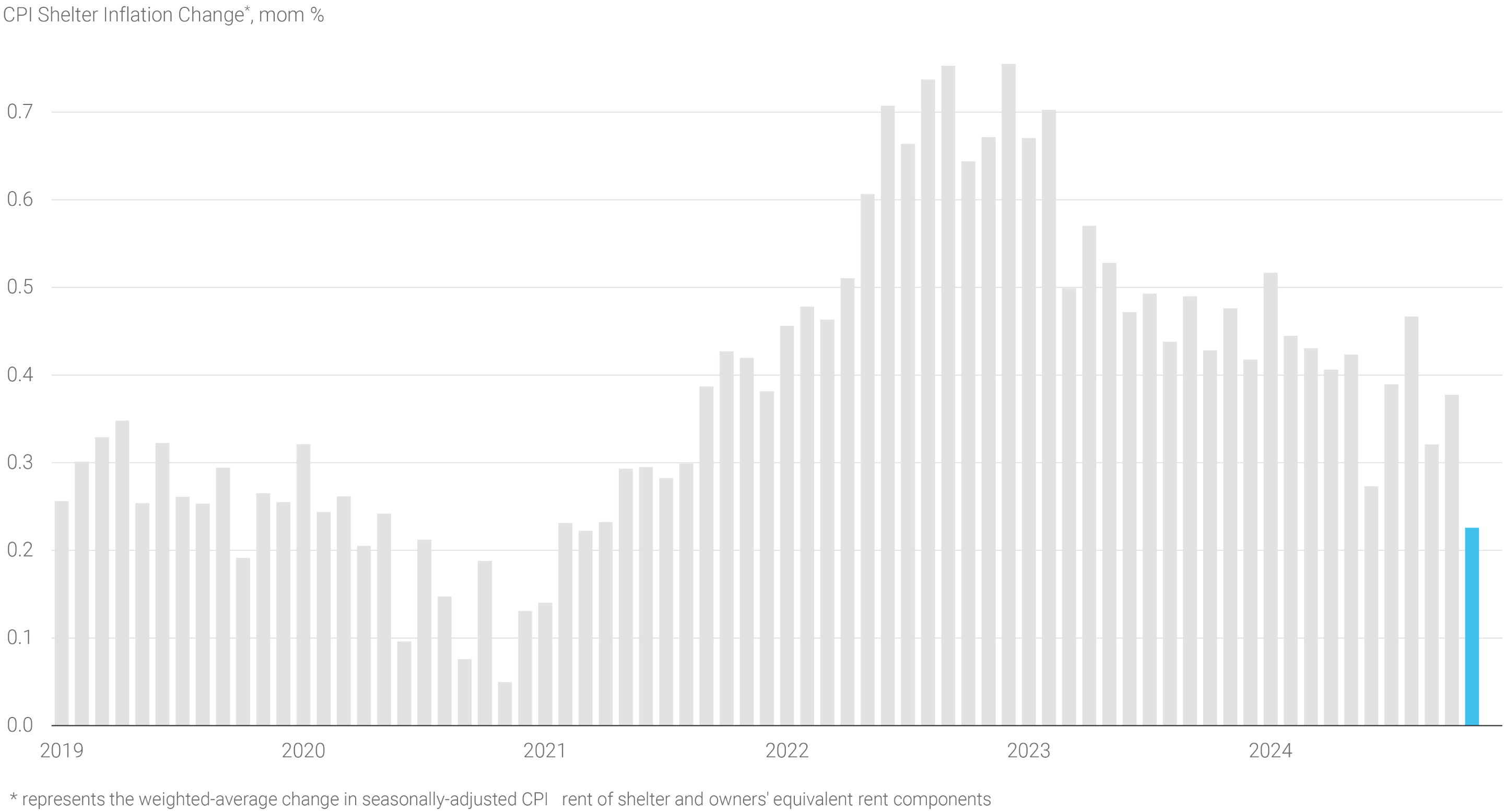

As discussed in our prior note, recent months’ inflation prints have been on the firmer side even if the details were more favorable than the headline. The latest readings indicate that overall inflation remains stubbornly above the Fed’s 2% target. On the brighter side, as shown on (see panel 1), shelter inflation slowed meaningfully in November, with the weighted average of owners’ equivalent rent and rent of shelter increasing at 0.23% month-over-month (mom) -- the smallest monthly increases since early 2021. Moreover, inputs to the Fed’s preferred inflation gauge, the core PCE price index, were relatively muted, with November’s 0.11% mom increase in the core PCE deflator representing the smallest monthly increase since May. Nonetheless, the annual core PCE inflation rate remains at 2.8%, failing to make meaningful progress in recent months. This is the primary thorn in the outlook for the economy: while activity has remained healthy, inflation has failed to slow closer to the Fed’s target, leaving officials anxious about whether monetary policy is restrictive enough.

Panel 1:

Shelter Inflation Slows to The Lowest Monthly Gain Since 2021

Labor Market

The labor market remains healthy even if signs of a gradual cooling persist. The U.S. economy added 227,000 jobs in November driven by a reversal of hurricane-related job losses in the Southeast and the conclusion of the Boeing labor strikes. Additionally, the October report was revised slightly higher, helping the 3-month average job gains to improve to a healthy 173,000. Nonetheless, the unemployment rate rose to 4.2% in November despite a drop in labor force participation; that is, the jobless rate rose despite fewer individuals looking for jobs. Job growth continues to be concentrated in the healthcare and private education, government, and leisure and hospitality industries, which together accounted for nearly 75% of the payroll growth in 2024. These data suggest the labor market is in a good position overall but highlight risks that external shocks, such as an increase in labor market entrants, could be difficult to absorb and could lead to a more meaningful deterioration in the employment picture.

Altogether, economic growth remains robust, driven by healthy consumer spending and a steady, but cooling, labor market. The strength in demand has slowed the progress on disinflation, leading Fed officials to signal a more gradual rate cutting cycle in 2025. This marks a good starting point for 2025, which is expected to bring more of the same, but is also – perhaps to some larger degree than usual – filled with uncertainty including the impact of policy changes from the incoming administration.

Financial Markets

Interest Rates and Volatility

Treasury yields rose throughout December due to hawkish commentary from the Fed, strong economic data, and a challenging fiscal outlook. While the Fed lowered its target rate by 25 basis points (“bps”) at the December meeting, officials signaled that the pace of future rate cuts will likely slow, and the terminal rate will be higher than previously expected. As a result, interest rates increased, reflecting higher medium-term expectations for the Fed Funds rate, which had already risen sharply in recent months. For example, implied rates on Fed Funds futures for the end of 2025 have climbed to 3.92%, up from 2.95% at September quarter end.

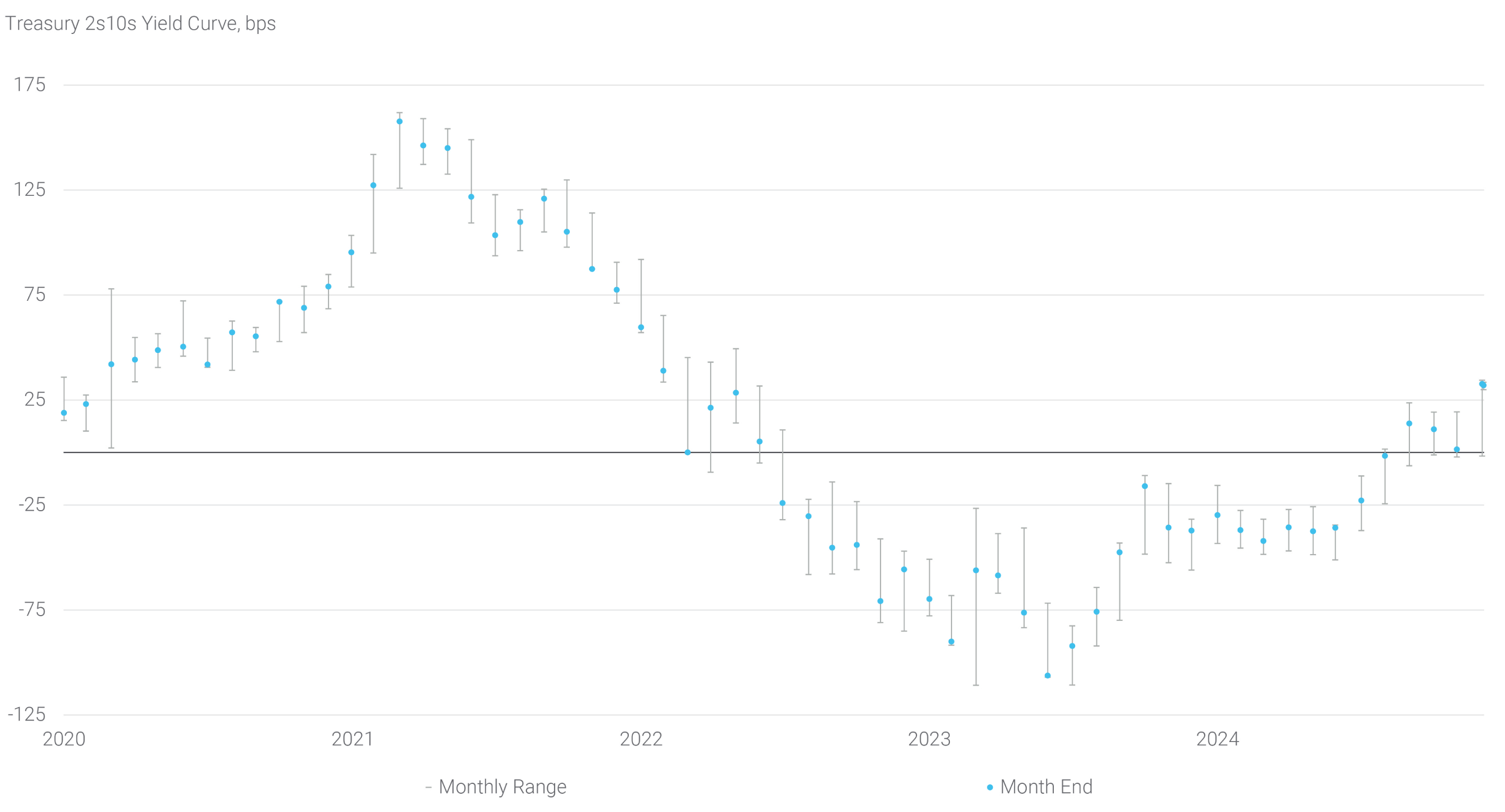

With markets pricing limited easing moving forward, the front end of the yield curve has adjusted closer to the current Effective Fed Funds Rate (“EFFR”). 2-year Treasury yields closed at 4.24% at the end of December, less than 10bps below the EFFR. However, the most significant selloff occurred at the long end of the yield curve, with 10-year yields rising 40 bps during the month and 30-year yields reaching a year-high of 4.82% in the final week of the year. This led to a notable steepening of the Treasury yield curve, with the spread between the 2-year and 10-year yields reaching a year- high of 32 bps, ending the year 70 bps steeper (see panel 2). Implied interest rate volatility declined in shorter expiries in December following the passage of several risk events but was little changed over longer option expiries. Volatility continues to be largely correlated with interest rates, rising when rates increase, leading to continued historically elevated implied volatility. Furthermore, Treasury yields at the long end of the curve moved higher than swap yields of the same maturity, causing swap spreads to tighten.

Financing markets ended the year on a surprisingly calm note, with the year-end calendar turn experiencing orderly market functioning. The Fed’s auxiliary funding operations went unused, easing liquidity concerns that had been present in recent months and spiked around the Christmas holiday.

Panel 2:

The Treasury Yield Curve Steepened in December

Agency MBS & Credit

In light of higher long-term Treasury yields, agency mortgage-backed security (“MBS”) spreads widened in December as MBS continued to trade directionally with interest rates. The Bloomberg U.S. Mortgage-Backed Securities Index recorded a negative 17 bps excess return as the MBS market moved in tandem with the broader sell-off in rates. However, the impact of this widening was somewhat contained due to the steepening of the yield curve and a backdrop of relatively low supply in the MBS market. Overall, the curve steepening improved yield pickup, driving stronger investor demand for higher coupons.

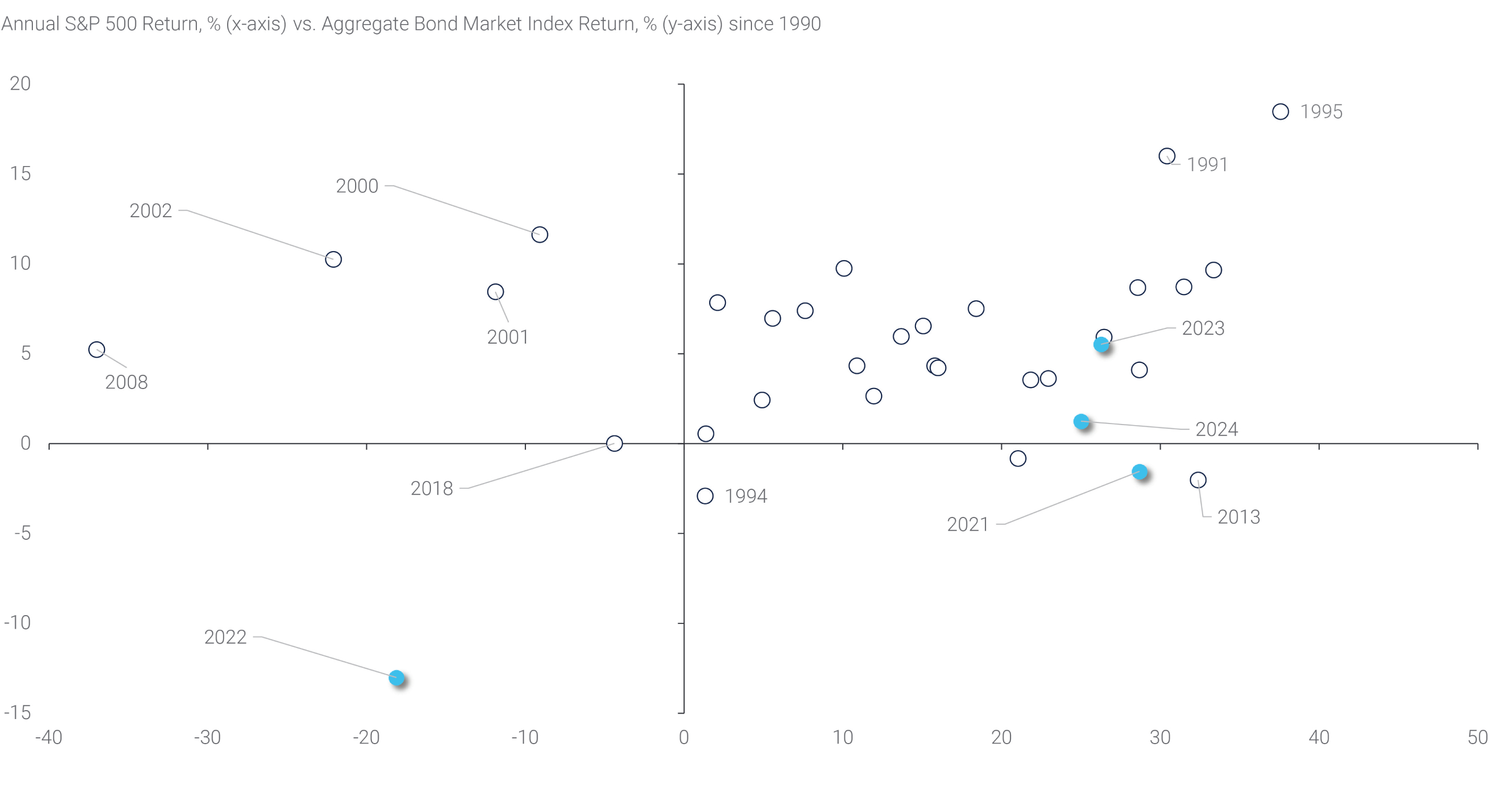

Meanwhile, corporate bonds once again outperformed other fixed income sectors in December. This capped an impressive year for corporate bonds’ relative performance, with the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Corporate Bond Market Index delivering an excess return of 2.46 % on the year, while spreads reached their tightest levels in many decades. Solid corporate earnings, strong economic growth, and a rise in yield-based demand domestically drove investors into the corporate bond market. More broadly, the fixed income sector narrowly posted a positive total return for 2024, with the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Market Index recording a 1.25% total return for the year (see panel 3).

Panel 3:

Equities Delivered Another Strong Year While Bonds Barely Stayed Positive

Equities & Currencies

U.S. equity markets reacted negatively to the hawkish Fed meeting and interest rate selloff, declining 2.4% in December for the second worst month of the year. Despite the December downturn, equity markets ended the year with an exceptional performance overall. The S&P 500 posted back-to-back annual returns of over 20% for the first time since 1998/99, and global equities marked their fifth annual gain in six years. The U.S. dollar also posted strong gains, with the U.S. Dollar Index (DXY) reaching a 2024 high into the end of the year. The dollar defied the typical weak December seasonality, realizing its best December return since 2009 at 2.6%. The strengthening of the dollar in December reflected the same themes seen in the previous two months, primarily a U.S. economy that continues to outperform other G7 countries.

The New Neutral

The U.S. economy has surprised to the upside for a second consecutive year in 2024, despite elevated interest rates. The strong performance has raised questions as to how the U.S. economy has managed to thrive despite the highest nominal interest rates since well before the 2008 great financial crisis (“GFC”). Potential answers lie in the elusive neutral rate, the long-term interest rate at which the economy is roughly balanced between optimal output growth, full employment, and inflation at the Fed’s 2% target. Higher estimates of the neutral rate suggest that the economy could experience higher output growth at a given interest rate level, all else equal. In other words, the Fed’s high interest rates, put in place to fight post-pandemic inflation, might not have been as restrictive to economic activity as previously estimated.

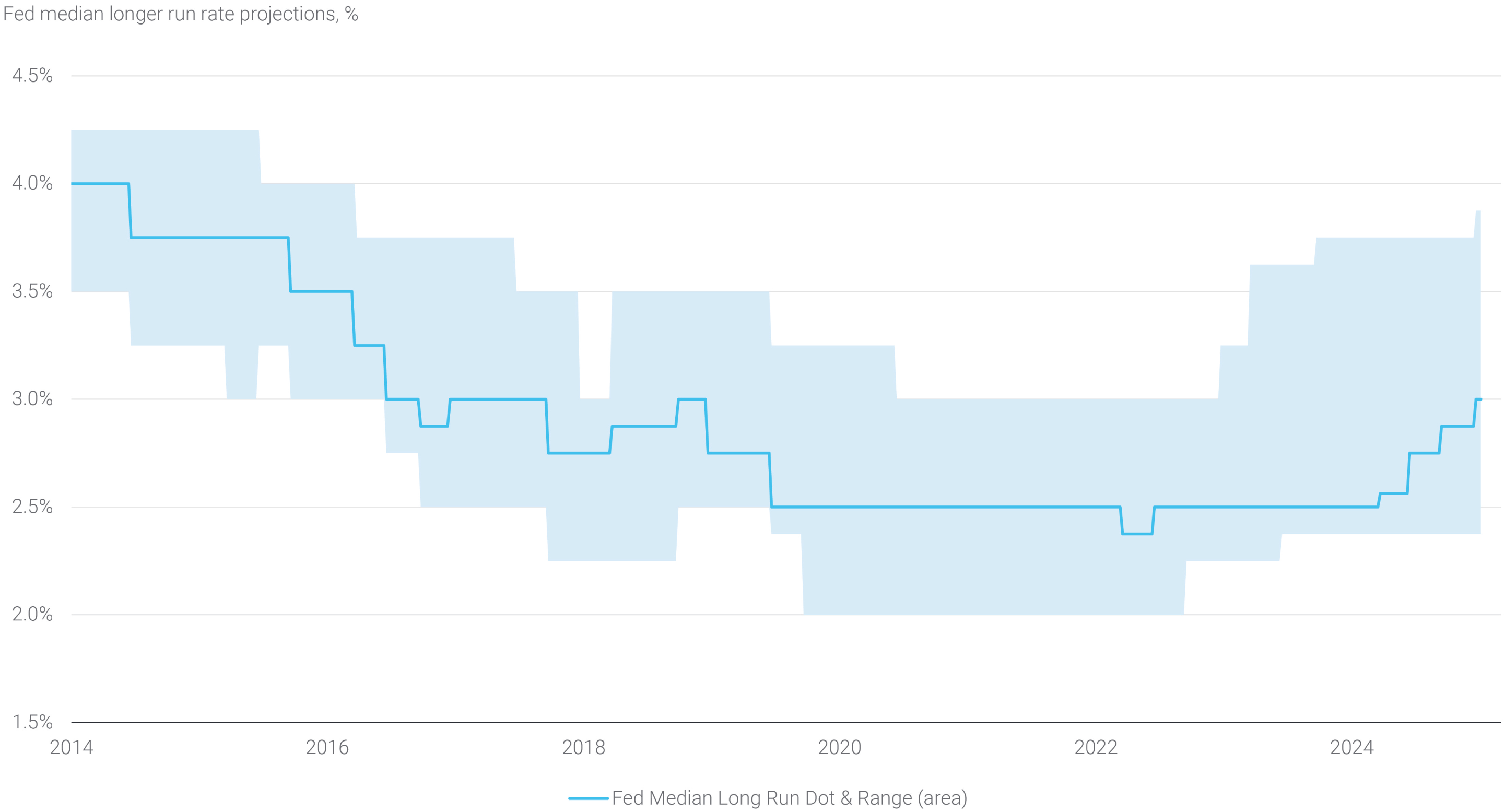

Despite its potential usefulness, the neutral rate is difficult to observe and typically estimated through academic research methods, which can add further complexities.(2) A closely watched approximation(3) comes from the Federal Open Market Committee (“FOMC”) itself via its SEP, which showed a 3.0% median estimate for the long-term Federal Funds rate in the December forecasts. Along with the median estimate, which has risen in recent SEPs, the divergence between individual Fed officials’ forecasts has also risen. The lowest forecast has remained at 2.375% for the past 18 months, while the highest estimate has now risen to 3.875% (see panel 4). The resulting 1.5% range among estimates is the widest since officials began publishing their estimates in 2012.

Panel 4:

The Fed’s Longer Run Rate Projection Rose in 2024

The increase in the neutral rate has been driven by robust productivity growth, which has benefited from better post-pandemic labor matching, corporate investment, and automation efforts, and – perhaps – early payoffs from adoption of artificial intelligence solutions. As more of these benefits come to fruition in coming years, productivity growth is expected to remain strong. Meanwhile, larger government deficits and stronger demographic growth from immigration could also have contributed to the rise in the neutral rate.

We expect the discussion around the neutral rate to remain prominent into 2025, particularly if the economy stays strong and along its soft-landing path. If the neutral rate has indeed risen, it would change the outlook for the current Fed cutting cycle. Assuming the neutral rate is higher and more in line with the period before the GFC, the period between 2008 and the COVID-19 pandemic would represent a time in which interest rates were artificially depressed by transitory factors including the need to repair balance sheets following a meaningful financial crisis. Notably, much of the discussion during the period pondered a new normal in which structural changes had caused interest rates to be permanently lower. Currently, the period between GFC and pandemic looks more like an outlier than a new normal, though further passage of time and assessment is needed. Assuming this thinking holds true, a higher neutral rate would result in earlier cessation of the current rate cutting cycle. Markets are fully embracing this narrative, with the Fed Funds futures market pricing an end to the cutting cycle above 3.5%.

A higher neutral rate would also imply structurally higher interest rates in the future. This would be a major positive for fixed income investors that would be compensated through higher interest income and wider spreads. However, elevated interest rates also place a greater burden on debtors, most notably the U.S. government, particularly when considering its current deficit trajectory. We therefore expect the neutral rate discussion to stay in focus over the near term, reflecting the dichotomy between healthy U.S. economic growth and increasing debt burden.